Kia ora from Marianne,

Unless you’re an essential worker (in which case, thank you!) you’re probably trying to work from home right now. Which is difficult in different ways for each of us. But we’re doing it. We’re staying home. Parenting and caring for others. Juggling all the things. Worrying we aren’t doing any of them well enough. Missing the people and places we love.

Why are we all doing this hard thing?

One of the strongest motivators for all of us to stay home right now is knowing that this is the best thing we can do to keep everyone in our communities safe and well.

We are doing this because, despite our differences, most of us care a lot about each other.

In our Narratives for Change workshop, we show a graph of the values prioritised by people in a representative sample of New Zealanders. It shows that the vast majority of people in the sample prioritise our shared wellbeing more than personal success, and caring for each other and the planet over accumulating wealth or social power.

This helps to explain why clear messaging that frames staying at home as an act of care for others, has been so effective. But it also begs the question: if we all care so much about collective wellbeing, why is it so hard to get support for some of the changes that will make the biggest difference to people and the planet?

Part of the answer to this question is that we all hold many different values, and the context in which we are making a decision significantly influences which of these many values we prioritise in that decision. People will make a decision using the value that has been brought to the surface for them.

For example, if I have been repeatedly told that the reason I should care about climate change is the economic cost of inaction, then when I make decisions about my support for big climate actions or policies, I’m likely to consider them in terms of money. Research has shown that thinking about the economic cost or benefits of a decision is more likely to motivate me to do things for my individual personal benefit, and less likely to motivate me to support things for collective benefit.

What this means for people trying to deepen public understanding of complex issues and build support for the big changes that will make the world a better place is that we should always offer people intrinsic, collective reasons to care and act.

This month’s newsletter has a selection of articles and reports from our own research and others’, which will give you concrete examples of how you can use intrinsic, collective values to motivate people and build support for those big changes that we need to make for our shared wellbeing.

Take care,

Marianne

Crafted at The Workshop

Talking About Early Brain Development in Aotearoa New ZealanD

The Workshop has developed a report on how to talk about early brain development in Aotearoa New Zealand to build greater awareness of brain development and how to support it in the early years. This was commissioned by the Child Wellbeing Unit of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and followed a two day brain development collective wānanga held in March 2021. The wānanga brought together non-government service providers and designers, government and philanthropic funders.

The purpose of this report is to provide a partial map of the current territory of public narratives and mindsets around early brain development, explain guiding principles for deepening understanding of the issue through more effective narratives, and propose some communications strategies. We have also recommended some potential next steps in this narrative shift work.

You can read the full report here:

https://www.theworkshop.org.nz/publications/talking-about-early-brain-development-in-aotearoa-new-zealand

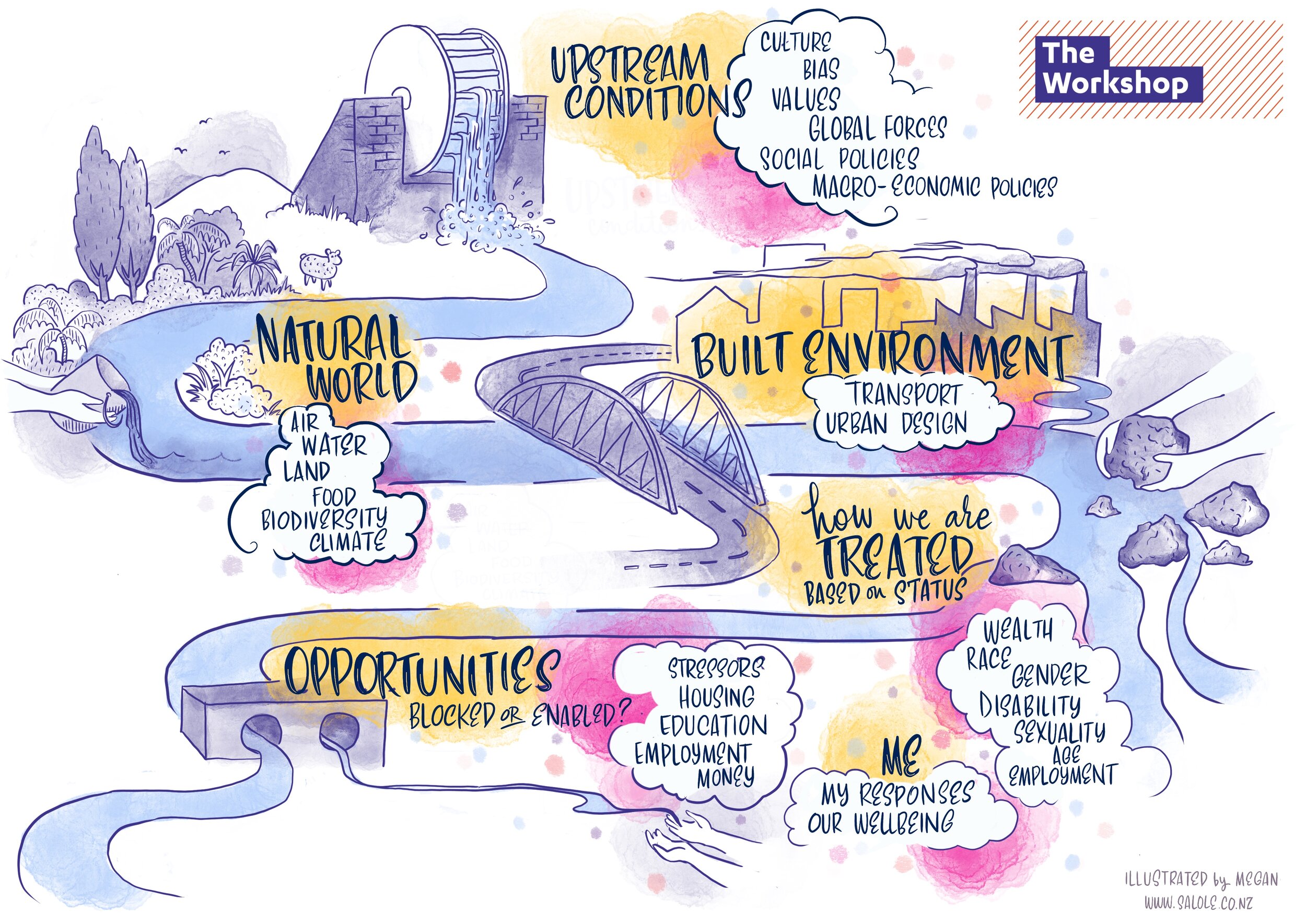

Reframing systems change: Changes that make the biggest difference

Throughout our research project ‘How to Talk about Systems Change’ we heard about how everyday life could be much better, for so many more people, once the changes we are working toward have happened and our human-built systems have been redesigned to prioritise people and te taiao. We were reminded of how critical this work is, yet how challenging it can be to communicate.

To get there, the knowledge holders we spoke with identified the need to build a shared understanding of what systems change means among our community of practice. In our upcoming report, we follow the framing advice of UK researchers in reframing systems change as the changes that make the biggest difference - and offer the upstream/downstream metaphor of an awa or river as a way of explaining the changes we are working towards, and why they are important.